Your feedback and comments are appreciated. See Contact page for e-mails.

Resisting Documentary Photography

by Richard Rivera

When most people pick up a camera it is to document people and places—to record events as they occur. This is the seductive aspect of photography which often becomes an imposing limitation for Fine Art photographers.

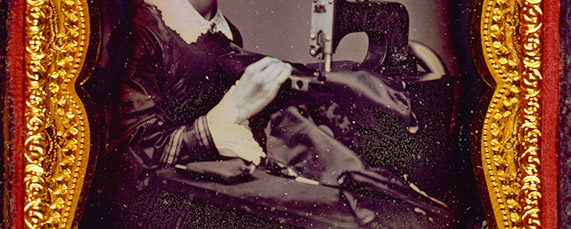

From the earliest experiments of William Henry Fox Talbot and Louis Daguerre in 1838 the photographic impulse was to reproduce the natural world as it appeared to the naked eye. In 1838 recording events as they occurred was not seen as a limitation. In fact it was, and remains, an astounding and wondrous achievement. It was a breakthrough from the limitations of time and class distinctions—time, in that photography recorded an instant of time and held it for eternity; and class distinctions whereby only the wealthy or royalty could afford portraiture.

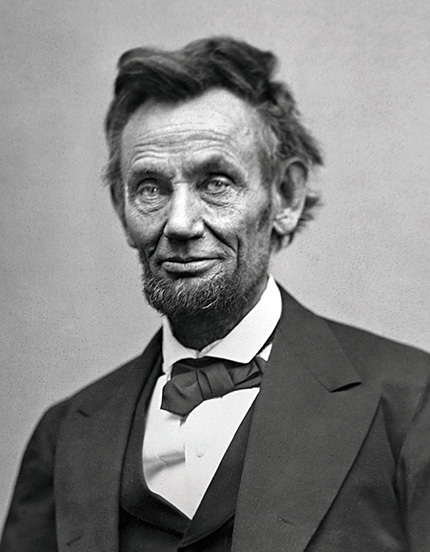

By 1856 photography had becomes so prevalent in the United States that it was possible for a middle-class person who had saved two weeks wages to obtain a medium-sized daguerreotype portrait.* Less than ten years later photography had become so universal that it was used to record the horrors of the American Civil War, and also repeatedly used as an official way to immortalize Abraham Lincoln’s visage instead of a painted portrait.

Today, photography is still used primarily as a recording tool for people, places and things. When we consider photographers that use the camera in this way we see that they have distinguished themselves from their fellow photographers through their choice of subject matter, style, and cameras.

The default view of the camera as a recording tool is all-encompassing and undiscriminating. This differs significantly from the way a person sees. A person’s “seeing” centers on details—the tilt of someone’s walk, the shadowed side of a face, the shaft of light that singles out one person in a crowd, the play of light and color at the bottom of a pool, etc. The challenge however for the fine art photographer is to move beyond the mechanical default view of the camera, and use the camera as just another tool to realize their artistic vision. To do so the artist must hone their “seeing” towards the abstract qualities of seeing as a person sees, rather than the literal undiscriminating eye of the camera. This revised form of seeing involves imagining the end result of the image you wish to create, as well as the post-processing needed, before pressing the shutter button. (This does not necessarily mean having a complete road map of post-processing. Creation is an intuitive process and experimentation is an intrinsic part of creative discovery.)

Fine art photographer Minor White (1908 - 1976) detailed the act of seeing and photographing in this way, “…the photographer… is showing us an expression of a feeling. But this feeling is not the feeling he had for the object that he photographed. What really happened is that he recognized an object or series of forms that, when photographed, would yield an image with specific suggestive powers that can direct the viewer into a specific and known feeling, state or place within himself.”**

The act of rebelling against the camera’s default view prompts some photographers

to gravitate to black & white as abstraction, others to push color rendition in new directions, and or others to devise ingenious ways of reshaping the machine to do

their bidding. (See examples and links at bottom.)

The orthodoxy of photography ushers us towards a black & white “realistic” view

of events as they occurred, and one that is highly suited to photojournalism. Artistic interpretation is (or should be) completely unbound by conventionality and opens

the floodgates of imagination.

Personalizing photography to reflect the artist’s vision of how an image should look rather than accepting the machine’s view is a journey towards a personal style. It entails much hard work, experimentation, and an in-depth knowledge of your tools to arrive at a thorough understanding of a what camera and processes can achieve.

Examples:

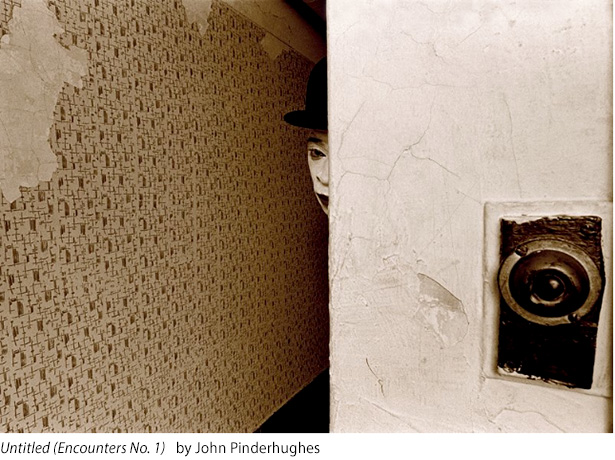

Untitled (Encounters No. 1) by John Pinderhughes

http://www.artspace.com/john-pinderhughes/untitled-encounters-no-1#

Seducers II (Orange) by E.V. Day

http://www.artspace.com/ev_day/seducers-ii-orange

Arrastre 3 by Ana Teresa Fernandez

http://www.artspace.com/ana_teresa_fernandez/arrastre-3

Approaching Dust Storm, Floyd County, Texas by Andrew Moore

http://www.artspace.com/andrew_moore/approaching-dust-storm-floyd-county-texas

Cowboy by Duane Hanson

http://www.artspace.com/duane_hanson/cowboy

* * *

* http://www.americandaguerreotypes.com/ch2.html

* http://www.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~gahchs/1856/Economy/

** EQUIVALENCE: The Perennial Trend by Minor White

Photographers On Photography —Edited by Nathan Lyons, 1969, Publ. Prentice-Hall, Inc.

The matter of equivalence was well stated in an essay by photographer Minor White who wrote, “When the photographer shows us what he considers to be an equivalent, he is showing us an expression of a feeling. But this feeling is not the feeling he had for the object that he photographed. What really happened is that he recognized an object or series of forms that, when photographed, would yield an image with specific suggestive powers that can direct the viewer into a specific and known feeling,

state or place within himself.”

October 12, 2015

Abraham Lincoln, February 1865, about two months before his death. Photographed by Alexander Gardner

-by-ev-day%20copy.jpg?crc=4086373953)

Camera Sense Archives

APRIL 2015

Book review

iPad software

Movie review

Underwater dual-use camera review

Photo commentary

Book review

PhotoTech commentary

The Interview, movie review

Photo enhancement or management

MAY 2015

Photo Tech commentary

Photo/Art commentary

Camera review

TV series review

JUNE 2015

JULY 2015

AUGUST 2015

SEPTEMBER 2015

OCTOBER 2015

Copyright © 2015 Richard Rivera & Rivera Arts Enterprises All rights reserved. No copying or reproduction of any kind without express written permission from Richard Rivera

Legal Disclosure Camera Sense and Eagles of New York are trademarks of Elk Partners LLC