Your feedback and comments are appreciated. See Contact page for e-mails.

Speeding Up/Slowing down

by Richard Rivera

One the most tragic losses of the late twentieth century is the inability to take the time

to reflect on our actions. I often hear people comment on how they don’t have enough time to do this or that, because they are so busy. Clearly, the number of hours in the day itself has not changed, but the perceived stress of accomplishing things quickly, or more efficiently, is certainly a factor and a major distraction for most of us. Especially those with school-age children who feel they are on a constant treadmill of activity.

Many are affected by the undercurrent of a faster pace that has increased exponentially over the past thirty-five years in conjunction with personal computers and the internet. The compulsion to respond immediately, to instantly view every email and text message, where urgency is more or as important as content, is pernicious, and we see the effects of it in our language and communications.

In PBS television’s

Ken Burns’ The Civil War,

we hear many readings

of letters from the mid-

19th century, that are

to-and-from soldiers in

the field, and relatively

uneducated men. In

listening to these letters,

the degree of articulation

and lyricism we hear is

astounding. Granted,

a great deal of it is repre-

sentative of the formal language of the age rather than colloquialisms, but one

can also intuit that a great deal of thought was given to the feelings that were

being communicated.

I feel that today the common language, especially the written word with its influence from texting and e-mail, has almost become a throw-away item that is given little thought or consideration—except perhaps in business transactions because there is money at stake. The proof of our hurriedness is the sheer amount of typos easily seen in online news media and magazines in contrast to forty years ago.

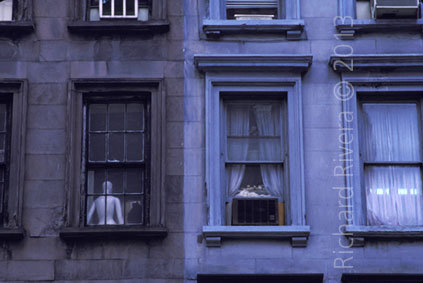

For photographers, it is

good to remember that

Henri Cartier-Bresson,

the man who is famed

with capturing the

“decisive moment” as

he termed it, and set the

standard for 35mm street

photography, worked

with a manual camera

and was a keen observer.

He took the time to

reflect and wait for the

appropriate moment.

There was no automation. Shooting at 6 frames-per-second was not an option.

Intrinsic to his process of capturing the decisive moment was observation and patience. For photographers, these qualities are just as pertinent today as they

were one hundred years ago.

Elliot Erwitt once said, “All the technique in the world doesn’t compensate for the inability to notice.”

May 21, 2015

Camera Sense Archives

APRIL 2015

Book review

iPad software

Movie review

Underwater dual-use camera review

Photo commentary

Book review

PhotoTech commentary

The Interview, movie review

Photo enhancement or management

MAY 2015

Photo Tech commentary

Photo/Art commentary

Camera review

TV series review

JUNE 2015

JULY 2015

AUGUST 2015

SEPTEMBER 2015

OCTOBER 2015

NOVEMBER 2015

DECEMBER 2015

Copyright © 2015 Richard Rivera & Rivera Arts Enterprises All rights reserved. No copying or reproduction of any kind without express written permission from Richard Rivera

Legal Disclosure Camera Sense and Eagles of New York are trademarks of Elk Partners LLC